University as Education

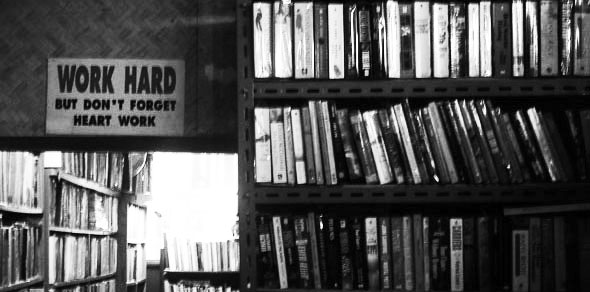

Heart Work, Carly Lewis

Heart Work, Carly Lewis

Education is something you pick up, day day by day, for just as long as you are alive. Or, perhaps better: Education is whatever understanding and attitudes you are wise enough to absorb, making them a part of your existence, during the relatively short time between your birth and your death.

Children, as well as animals, are trained. The training is imposed, whether through instruction, imitation and repetition, or because children anticipate various sorts of punishment for not doing as they’re told. At the age when the ability to reason is developing, a young person begins to learn what the elders place before them as important to know.

Then, leaving youth gradually behind, the young adult comes to understand that what is important to learn, what education is about, is nothing less than a fuller insight into the essence of that person himself or herself. Everyone begins life knowing nothing, entirely dependent. The infant, child, teenager is little more than an incredibly complex set of potentialities. Over time everyone comes, rationally, to realize that the most important fact of life is that everyone is an individual. And, despite all the similarities between individual human beings — which various “sciences” treat as all that matters—there are in fact only a few ways to mitigate the solitude of individual human existence.

How then, does education help an adult?

A good education, as distinct from training, sets out certain means for a person to learn what it is to be human. A baby possesses human potential. Whatever is given it, from a parent or society, amounts to either suffocation or a freeing of what it could become. Throughout the history of humanity, it has slowly discovered that potential is enormous. An adult must continue to learn, now using reason along with every other means, how he or she still shares, like a baby, in human potential.

To that end there are a number of ways that a university can help its students. But the various “disciplines” and courses can never do much more than scratch the surface in demonstrating the infinite number of facets of what a person can be and can do.

A student is in a course not just to memorize historic dates, rock formations, physiology, inorganic compounds, counterpoint, bacterial etiology and verb forms, but to relate that information to his or her own existence as the only individual in the entire world able to discover and develop more of his or her own personal potential in the years from the present onward.

Ideally, an education will present many examples of what human beings are, what they have become and what they have been able to do, over time, up to today. The student should begin to understand more clearly the nature of the world in which he or she lives, and how his life will certainly be influenced by it. The examples should set out the “good” as well as the “bad” in the world or in humanity, present acts or achievements that are exceptional or entirely mediocre, common among people, or commonly abhorred.

Those examples or illustrations, when set out in a formal “education”, present only a remarkable norm, whether high or low. They show only what humans have done and have on occasion become. As such they mark a particular realization of human potential.

But every person must alone discover that human potential, because it exists only within the individual alone. The examples will serve as an education only to the extent that the student learns to look closely enough at the substance of the examples to understand what each demonstrates about what he or she can do or be. The lecturer can do that only to a very limited extent. It is up to the student to listen to the case the lecturer presents, to go away, seriously read about the case, and think about how it sheds significant light on the relation between each human life and the world.

The real value of any case presented by a lecturer is drawn out by a student who sees how it applies in any degree, to him or herself as a human being. Reflecting on an example of how human behaviour should foster a student’s understanding of what he or she can be or can do. Furthermore, a student’s classroom presentation, case study or essay is an indication of how well the student has “taken in” the material, has made it his or her “own”. The clarity and soundness of a viewpoint or argument in a student’s coursework is a distinct measure of his or her perception of the value of the case to human life.

What university is about is not just teaching and study, but primarily about learning. A student at university has a chance to begin to learn — to perceive — a little of what a human being is and what the student, as a single, solitary human being in the world can be.

The student will begin to learn to work alone or cooperatively, looking for reasons and links between ideas. (A well-cultivated memory is an invaluable asset in relating apparently dissimilar things; in that work, Information Technology can be a meretricious detriment.) The student will discover a critical attitude and will learn to make it habitual; by nourishing the skills of reason and logical analysis, he or she will question the reality, or solidity, of things that seem, or are made to appear, to be true. At the same time the student will form a habit of distrusting faith: human history has too often been shaped by simple answers and efforts to capture a person’s belief and to still his or her inquisitiveness. Motives, however innocent, are rarely transparent or pure in any person.

But the student will also learn that the process of meticulously careful reasoning has a vital counterpart: imagining and dreaming, carefully tended, may well lead to discoveries. The student should be encouraged always to be open to new ideas, new possibilities, unsuspected relationships between things. Analogy is the vital conduit when human beings learn: the faculty is instinctive in an infant; it should remain vigorous, as an initial impulse, in an adult.

Because a person represents only a minuscule sample of humanity, communication is a yearning that is both natural and necessary. Any attempt to bridge the gap between one’s self and other selves comes with more dangers than just about any other human activity. A student begins to learn just how important clarity is in the organization of thoughts and in the use of language. He or she may begin also to see that sympathy, a misty, necessarily imprecise understanding of the other individual, helps bridge the gulf, as does a growing understanding of the risky sense of trust and love.

Hopefully, as all this has suggested, a student will nourish the habit of never merely accepting what he or she is told is the truth about any person or thing. Above all, the university graduate should have begun to learn to think about the meanings of “good” and “bad”. A philosopher, a steel worker, an advertising executive, a priest or a teacher may each claim to have the ultimate answer about “good” and “bad”. But only the individual, living his or her own individual human life, can look for, and over time gradually refine, an understanding of what those supremely human perceptions of “good” and “bad” really are.

A student at university should never think that three or four years spent there result in an education—that upon graduating, he or she has “received” an education—as if it were a possession, to be taken away or to be self-satisfied about, an acquisition as neatly packaged as a prettily beribboned diploma. A student doesn’t “receive” an education: a student is exposed to a chance to discover a little about the enormous potential that is in humanity. The potential is waiting already in all neonatal human life. But much more importantly, it is still waiting in the student. It is a potential within his or her brain, heart, spirit and body, waiting only to be recognized and used, nurtured and developed.

Life will offer times of enormous variety of occasions, for an individual to discover and expand that unlimited inner potential. Those times will present both problems and opportunities. Of the problems, the scope is wide: suffering, fatigue, hatred, isolation, mysteries and uncertainties of all sorts. Those will call for courage, curiosity, stamina, self-reliance, empathy and sacrifice.

On the other hand, the opportunities that life offers may relate to beauty – in nature, in music and the arts, in a relationship with another person, in simple play – that arouse imagination, sensitivity and profound joy.

And that is what the graduating student has the rest of his or her existence to do: to exploit to the fullest the potential of being born a human being. Every moment in life can present an invitation to discover something of the infinite potential that is in an individual’s life. A successful university education will have awakened the graduate to a few of the means to undertake that lifelong adventure.