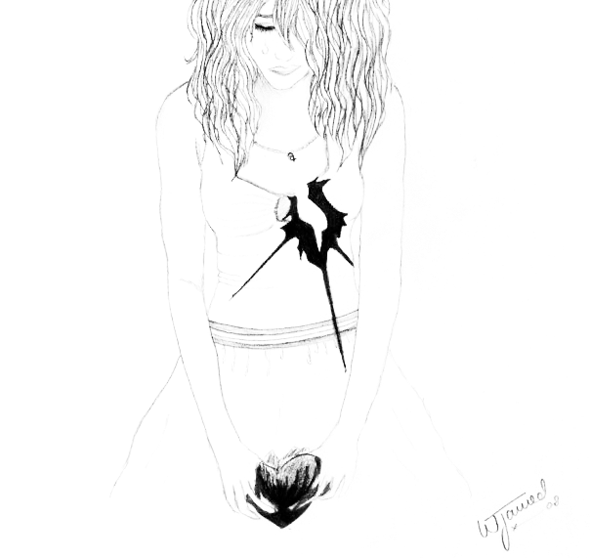

The Regret of Death

Incomplete, Wafaa Jawed

Incomplete, Wafaa Jawed

My grandmother was diagnosed with late stage breast cancer over a year ago. For some reason, the late night phone call still came as a surprise. She’d been taken to the hospital, unable to move or speak through the haze of the morphine drip. I don’t know what her last words were, or what she felt as she passed. When my grandmother died, I was 8000 miles away and two years removed from the last time I had seen her.

That was August. I braced myself for the inevitable grief of loss the day I heard of her condition. I expected some kind of throbbing, relentless grief to overcome me the moment I heard the news, something theatric and profound. What I didn’t expect was regret. Not in the way that I feel it now. All I can think about is every phone call I never made and every “I love you” I never said. After she was diagnosed last year, my mother and sister made the flight to Colombo to be with her. I was in the middle of fall finals and decided to stay in Waterloo. It seemed like a perfectly reasonable decision at the time. The reasoning behind it seems blown to shit now. I could have deferred an exam. Hell, I could’ve failed them.

Either seems preferable to not being able to remember the last thing I told her in person. In 20 years, I saw my grandmother less than a dozen times and every missed opportunity now feels like a Weight on my shoulders.

No regret weighs heavier on me than wondering if she really knew what I felt about her. My grandmother spent her life as a nurse, dedicated to the care of others. She worked with landmine amputees, refugee orphans, and single mothers. During my last visit, she took me along with her to an open clinic she had organized which offered medical care to Sri Lanka’s countless poor who struggle with a degree of poverty which I can barely even comprehend. I used to wonder how anything I did in my life, any degree of personal success, could ever measure up to what she did. By any standard my grandmother was a truly great woman.

And yet, I never spoke such words to her while I could.

Before she passed I wrote her a letter, not unlike this one, telling her these things. I figured she had a hard enough time understanding my American accent, and the things I wanted to say would come out clearer in print. Now I wonder if I’d have been better off making an inarticulate phone call while choking back sobs than corresponding through the sterility of the written word. I’m left wondering if she really understood what I meant to say in that letter or if it just came across as distant and pretentious.

From all of this it almost seems as if the things I’ve learned can be summed up in tidy clichés. The sort of plain truths I once thought were trite platitudes make far too much sense to me now. Appreciate the incalculable value of every second you have with those you love and never hold your tongue when it comes to baring your emotions. Our lives are so tragically finite and fleeting, the brief overlap of time between our existence and that of those we love even more so. Forget any illusions you have of immortality; of having another day or another week or another year to say what you want to say and do what you want to do.

Be honest, be real and never let death leave regrets in its wake.