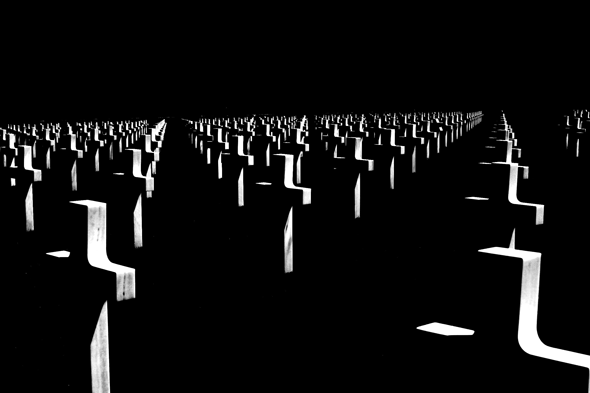

Name in Stone

The Price of Freedom, Nick Lachance

The Price of Freedom, Nick Lachance

The southwest portion of Calgary, Alberta is defined by what looks to be a large wildlife area around the Glenmore Reservoir. The enormous size of this area nearly brings a stop to the urban sprawl, cleaving the city before the north portion circles down to collect the long column of suburbs that is the south. Ten years ago this area would have almost mirrored the size of Calgary completely, stretching its long wooded limbs straight towards the Rockies. This land is called Sarcee 145, or The Tsuu T’ina nation. Eight years ago my family moved into a new community a stone’s throw from the barbed-wire fence where Calgary zoning ends and the nation begins. I spent most of my adolescence petrified that my house had been built on an ancient burial site. Maybe it was how the coyotes howled at night, or how the moon always shone gold, but logic be damned, I believed it!

For years, the city of Calgary has been attempting to negotiate with the residents of Tsuu T’ina for a land transfer that would allow the building of a freeway to connect the southwest and south portions of the city. Chief Sandford Big Plume, whilst attempting to explain to the Calgary media the difficulty of the decision, mentioned that the stretch of land has emotional significance for band members: “Negotiations are complicated because the stretch of land at issue is considered sacred and some of it contains burial grounds.” I’m sure you can imagine the extent to which my mind was blown! It was with those words that Chief Big Plume ignited in me an incredible curiosity and questions that would begin a personal obsession.

What do we owe our dead?

Who is responsible for the preservation of burial sites?

Do these burial sites matter?

Who do they matter to?

Is it only the living that care about burial sites?

What happens when the living who care die? Does the burial ground lose its significance?

If burial sites mater only to dead people, what kind of control do they have over their space?

And most important, what kind of wrath am I to expect for watching chick flicks and eating Freezies on the resting sites of Chief Plume’s ancestors?

Fleeing Calgary, as I did last year, should have eased any fears of posthumous stalking. Unfortunately, my concern only became magnified as I began to explore the beautiful southern Ontario countryside. This is a province absolutely littered with burial sites! Think about it: each one of your towns and cities has at least one historical cemetery. In addition, rural areas have graveyards from townships that are long gone, not to mention the eons of burials preformed by the Iroquois, the Algonquin, the Wendat and countless traveling Aboriginal bands. Add the countless lives of sailors and traders lost to the depths of Lake Huron, Lake Erie and Lake Ontario, and the worrisome commonality amongst most of these dead folk is that their burial sites are non-existent, unmarked or derelict.

There is no doubt about it: southern Ontario is a haunted place and the scant concerned parties seem to be myself, a bunch of dead people, and surprisingly, the government of Ontario.

Judging by its website, the Ontario Ministry of Culture is concerned about cemeteries for two reasons. For one, cemeteries are a cultural resource; they connect citizens with their history and the people who made it. Secondly, the government is harboring some guilt. It seems in the twentieth century, for reasons relating to urban planning and well-intentioned conservation methods, Ontario did a fair amount of grave moving, creating mass graves, neglecting to assemble whole remains, and permanently damaging irreplaceable headstones. These mass graves are identifiable by their assemblage; a regular graveyard will have its headstones a fair distance from each other, one could say a body-sized distance, and it usually will have families grouped in the same area. The Government’s relocated or ‘preserved’ cemeteries have their headstones grouped in one row or cluster. These resting places were gathered, as described by one pamphlet distributed by the Bruce County Museum & Archives “with no consideration for the original plan of grave arrangement, especially family groupings. Many have been relocated with little regard for their relationship to the original cemetery.”

Recently, the Ministry of Culture has moved to change its ways and rescue the remaining Ontario cemeteries. In the past five years they have released a publication called Landscapes of Memories, which describes how to properly preserve historic gravesites; they also set up a resource office that gives advice and recommends skilled workers. With assistance from this office, municipalities have been able to offer classes to volunteers and church groups who aim to tidy up the resting places of their forgotten dead.

What do we owe the dead? How do we want to be treated posthumously? To some these questions mean nothing, to others these questions are linked to deeply entrenched beliefs and expectations regarding their afterlife. The only thing we can be certain about in this discussion is our complete inability to control how our dead have been treated in the past and how we will be treated in the future; in both of these situations, we are not alive.