Learning

Image by John Clements

Image by John Clements

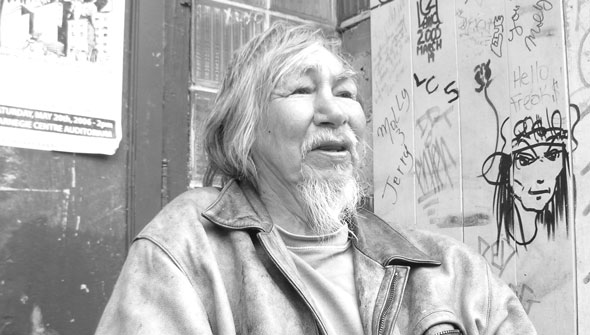

The expression on Brad’s face quickly turned into one of sadness and pain. The wrinkles on face and the look in his eyes showed that Brad had been through more than his fair share of rejection and pain in his life, and the question I had just asked was making him relive hard memories.

Brad had just finished telling me about his childhood and his days in the Yugoslav army. Born and raised in Yugoslavia, Brad was proud to fight for Tito and communism. “In those days,” he said, “we felt like we were actually living for something, together we were fighting for a better life.” Then, I asked him why he came to Canada. And, with the look of sadness and pain in his face, Brad sketched his escape from the ethnic violence that was tearing apart his country. But what Brad found in Canada was not much better than the world he had just left. Shortly after Brad came to Canada he started suffering from what was later diagnosed as schizophrenia.

The disease prevented Brad from being able to maintain employment, or establish a solid foothold for himself in Canadian society. His schizophrenia and lack of social supports left him to weather a spiritually and sexually abusive church leader, the chaos of our under-funded dysfunctional mental health care system, the nearly non-existent social support programs of Ontario and finally the streets of Kitchener.

In the two years that have passed since I met Brad I’ve learned many things. By the time I had started talking with Brad, he had been in Canada for more than 15 years; I learned that the values of democracy, freedom and individual rights that our politicians proudly proclaim have done little for him in that time. Brad has an experience of life that is very rarely engaged with academia, politics, business or any other public measure of power in our country. As I’ve gotten to know Brad and his life, I’ve realized that he and his story carry great lessons for us to learn. But unfortunately, Brad and his story are inevitably left out of the narrative of most Canadians’ lives.

I think that this fact might be okay, if Brad’s story was completely unique; a rare exception. But I have discovered, through my experiences at St. John’s Kitchen in Kitchener, in Vancouver’s downtown east side, and in poor areas of Scarborough, that this is simply not the case. The stories of the forgotten, of the poor, oppressed, afflicted, lonely and the broken leave me with the burning question of, ‘How do I honour them?’ Even worse, the friendships I’ve formed with Brad and a few others in Kitchener have forced me to examine what it means to love “the other”. You see, increasing the Ontario Works and ODSP rates may help, but what Brad needs is people who willing to take a risk in being in relationship with him. Not just psychiatrists, social workers or nurses, but rather people who just want to be friends and are willing to endure all the shit that friendship entails. It’s really just people who are simply willing to remember Brad and his story as they live their lives.

That idea is new and revolutionary and the great thing about it is that its not a hopeless one. It’s simply a more fulfilling expression of what it means to be human. There is no bureaucracy to navigate, no tuition dollars to pay, or quorum needed, all that’s needed is a willingness to meet someone and hear something new.