Disconnected Roots

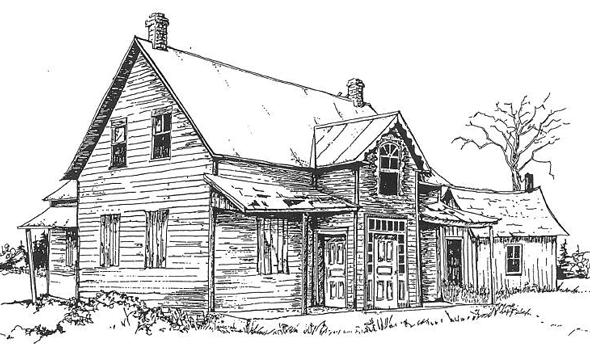

Image of the Original Borutski/Borucki Homestead

Image of the Original Borutski/Borucki Homestead

I have a photocopied handout of my family’s origin that was passed around at a 1994 family reunion: The Borutski family reunion. I didn’t attend because I was so small and unaware of where they—my family—came from. They came from Round Lake; that is all I ever needed to know. In this handout, something of which I have poured over many times since it was given to me a year or so ago, reading and re-reading it, I discovered the origin of my family on my mother’s side. I saw the first house built by my great-great-great-great grandfather and his dozens of sons. I read about the lives of these people I am so distantly related to and where they ended up. Some of them ended up buried in the ground before they could do anything significant with their lives. Some had dozens and dozens of children of their own and many of them lived for a long time to go on and have their own babies and farms. The postmodern cynic in me says that there is no such thing as an origin but the historian in my blood craves the knowledge of their exact starting point so it can validate my own existence. Because that is why we pay so much attention to family heritage and trees and personal stories – this is what it’s really all about. Each person has a set lineage and history that they take on the moment they are born. They have a mother’s side and a father’s side, plus a plethora of other perspectives and stories from deceased individuals. I am missing the other side of my history.

The town to which I am referring that holds all the secrets to my history is Round Lake, Ontario. A few minutes drive away from this place is the first Polish settlement in Canada: Wilno, Ontario. My great-great grandmother lived in a small house next to this massive Catholic Church that is both gorgeous and ominous. Round Lake, too, came to have a very large Polish population, if not the majority of the approximate 250 residents (on a good day) that are living there today. My grandmother’s family and my grandfather’s family—from Renfrew, Ontario— came together over time and they all bounced around from one Northern Ontarian town to the next, until settling back in a place named after a lake that is not very round at all. My grandmother likes to tell me about what kind of Polish we are, which is to say Kashubi. Before strict borders and nation-states, the distinction of territory that we know of now was far hazier during the latter half of the nineteenth century when my family immigrated to Canada. Our family hailed from Prussia but with connections to other parts of Eastern Europe and possibly from the Baltic or deeper Germanic regions. I joke and say I am not really Polish to my Polish friends but apparently, I am. I am whatever I want to make of where I come from.

I never learned Polish. I know one word and I don’t even know if it means apple or potato. But I have stories from the people that came after my very distant relatives and they have even older stories and it goes on. I have stories from my great-uncle going to Woodstock in 1969 and really being involved with the liberal movement’s characteristic of the 1960s that I can only dream about. I have a great-great uncle down the line who was a Canadian POW in a German concentration camp who stole Nazi books with pictures of inmates and corpses. He adopted two displaced Jewish children after the war. I have an expansive family history and all of that, whether or not I am truly conscious of it, is in me somewhere. It is in these very stories that I am relaying back to you. I am partly made up of all of this and more.

But I do not know where I come from on my father’s side. The unfortunate part about estrangement from family is not really knowing the rest of your own story. I don’t like that a giant chunk of my story is missing; it’s unsettling and always leaves me wanting to learn about everyone else’s to fill this metaphorical void in me. I know a few bits of my roots on my dad’s side but they are disconnected, fragmented, and possibly false. The same can be said of what I know from my mom’s side of my family, because history is subjective to whatever it is referring to and people inherently embellish for effect, but I have more footing with them; I have access to those histories if I want them. When my parent’s split up a decade ago, the connection I had with my father’s family was severed forever. They do not speak to me; I do not speak to them. They live in the same town as my grandmother, the very place my parents were born, but I do not see them. I don’t think they would even recognize me now.

Here is what I know from that side: I am Scottish. My grandfather is Scottish and his father married a native woman. So I am native as well. My step-grandfather is Irish. I am not Irish. This is what I know from my father’s side. When I tell people that I am native they look at me a little perplexed because I cannot answer the question about which tribe or group I have connections to. It seems ignorant, and to some degree it is, but it is just inaccessible for me to know that information. I have to guess. So far I have come up with Algonquin or Métis. But I do not know, nor will I ever know. My grandfather left my grandmother when my dad was only a baby. He lives in Montreal (maybe). I have twin uncles (maybe). My story is not so cleanly written on this side of my family tree. I fill up the space with questions and musings and quips about being from a rich Highland clan in Scotland, almost believing it for the sake of having at least something to grasp hold of.

I can list all of the ways I am connected to the great events and people of Europe, even claiming that my family was part of the first something or other to ever come to this country, but does this validate my existence? Am I, as a person, not taken as seriously because I only know half of my own story, my own history? I suppose that is not true in the least. It infuriates me that my punishment for circumstances I had no control over leave me with questions about who I am and where I come from, what I am connected to, but being mystified is quite liberating. Lineage seems to be less important these days than what it was fifty years ago. Even fifty years ago, it was not as strictly monitored as it was fifty or so years before that. Where my family has come from is significant to me as a person but it is no longer cause for a validation of self. My roots are all jumbled up and I am sure I am not the only one. I used to fret about it when people would talk about family reunions because they seemed more solidly whole than I was. This is no longer the case, because I am rooted, grounded and whole all on my own.