Creatures of the Night

Fangs. Garlic. Wooden stakes. Long black capes and pale skin. The visual iconography of the vampire alone has been sufficient to cement them into the public consciousness, arguably more than any other supernatural or horrific creature. But, beyond a disturbing visual, the longevity and vibrancy of the vampire legend can be attributed to a single aspect of the legend: their being ‘undead’. Though other creatures in the horror pantheon, such as the zombie, have portrayed life after death as cause for fear, vampires offer a unique overlap between the extremes of life and death. Moreover, while the grotesque, deformed figure of the zombie might suggest a terror or repulsion towards death, the sleek, seductive aesthetic of the vampire can be seen to represent an eerie fixation with the concept of death and afterlife, as if an alluring or perversely fascinating realm.

An explanation of changing perspectives regarding the vampire over time can be established through the figure’s ability to tap into cultural and spiritual fears. From its roots in folklore to Bram Stoker’s unforgettable novel Dracula that cemented the figure into public consciousness, it is easy to read Judeo-Christian allegories into vampire lore, evoking a Satanic figure of an emissary from Hell or the devil himself. This connection between vampires and the evil afterlife could explain the crucifix shape being fatal to vampires, as well as their natural awakening at night, historically the time where evil, Hellish figures lurk the world. The vampire figure came to represent a seemingly ‘living emissary of death’, which literally drains life out of its victims – a walking reminder of the dark punishments of death for those who did not live virtuous, holy lives. As such, the association between the horrific vampire and its deathly overtones could easily have contributed to a cultural fear of death, encapsulating all the religious fears and dreads into a single, unforgettable individual entity.

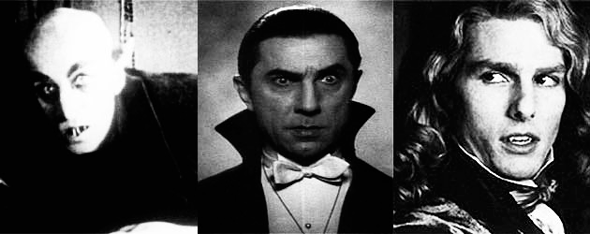

However, just as the 20th century led to a popularity explosion of the vampire in cultural texts, attitudes and depictions of vampires demonstrated a marked change from the Satanic figures of the past. While the titular Count himself was given his moments of sympathy and pathos in Stoker’s Dracula, the vampire was generally seen as a feral beast, consumed by its unnatural bloodlust and incompatibility to ‘normal’ human beings. The animalistic association was made even more explicit by folklore stating that vampires can actually transform their physical bodies into animals, including bats, wolves, lizards or apes. Such a derogatory attitude was reflected in early cinematic vampires, particularly F.W. Murnau’s timeless telling of the Dracula story Nosferatu, in which the title character is portrayed as a rat-like, deathly pale, and deformed figure who hovered around and literally withered and dissolved when exposed to light, as if more dead than alive.

Ultimately it was 1931’s Dracula film with Bela Lugosi that provided a turning point. While still undeniably the antagonist, Lugosi’s Dracula proved composed, suave, deadly seductive, and even slightly sympathetic, all the more frightening by how worrisomely human he seemed. And it is this ‘human vampire’ which modern popular culture has embraced, nearly universally, despite the occasional exception; Christopher Lee brought to life a more savage Dracula in a series of exploitation horror films by Hammer Studios, and recent graphic novel adaptation 30 Days of Night showed a rekindling of the feral, animalistic vampires of old.

And as the years passed, representations of vampires only continued to become more sympathetic and ultimately more seductive, particularly in cinema of the late 1980s to early 1990s. Particularly noteworthy examples included The Lost Boys, involving a group of ‘teenaged’, hip vampires (the film’s tagline even stated “Sleep all day. Party all night. Never grow old. It’s fun to be a vampire”); Interview with the Vampire: The Vampire Chronicles, based on the Anne Rice novel, which cast youthful Hollywood sensations including Brad Pitt, Tom Cruise, Antonio Banderas and Kirsten Dunst as bloodsuckers; and Francis Ford Coppola’s remake of Dracula, casting Gary Oldman as the titular Count, yet infusing the character with a previously unseen tragic back story and emphasis on a romantic subplot, turning the timeless antagonist into more of a pathos-ridden antihero. Through the recent spectacular successes of the Twilight and True Blood series, the vampire has only continued to skyrocket in popularity, particularly in female and teenaged demographics, which previously would have had significantly less interest in horror creatures. The sheer number of ‘Edward’ posters adorning the walls of young women alone can attest to the unprecedented level of vampires being seen as attractive, even pinup caliber.

But is casting young, attractive movie stars sufficient to reconcile the horrific roots of the character in the minds of audiences? No matter how ‘PG’ the vampires of Twilight may be, abstaining from drinking human blood and without the bestial transformations or withering in light, even Edward was literally mostly dead, only to be wrenched back into a shady ‘half-life’ by horrific desecration of his body by another vampire and is now forced to prey on the blood of other living creatures to survive. Edward is even wary of spending too much time around the human woman he loves, for fear that he will be consumed by his lust for her blood and turn her as well into a vampire. Thinly veiled allegory for teenage sexuality aside, how could such a condition reasonably be considered attractive?

One explanation can be to return to the inextricable connection between vampires and death. As cultural attitudes have changed through the years, the previous attitudes towards death as something horrific and terrifying, yet intangible, have also undergone profound changes. While it would be hard to argue that the majority of the population do not still fear death to varying degrees, there has become a more culturally discernible sense of inevitability entwined with peoples’ attitudes towards the phenomenon, that death is inescapable and people must come to terms with it at some point in their lives. Certain cases, including those who perform extreme sports such as parachuting out of airplanes, bungee jumping, or mountain climbing even demonstrate a seeming flirtation with the concept of death. Many who perform such activities speak of an exhilarating ‘rush’ they get, as if having cheated or temporarily ‘mastered’ death, suggesting a romanticizing of the concept, and the interplay of an individual with it.

This particular attitude can perhaps best explain the appeal of the vampire in contemporary culture. If the vampire represents death, it is an undeniably attractive, fascinating and even downright desirable representation, perhaps mirroring deeply seated or hidden attitudes towards the concept in the minds of the general public. Being undead, the vampire has literally ‘conquered death’ in a way that a bungee jumper never could, and such a fascinating sense of entitlement could easily outweigh the less desirable aspects of vampire lore. Vampires can be seen as allegorical for the strange, seductive fascination held by death, and their increasing popularity and steadily more positive representations could suggest that cultural attitudes towards the topic continue to be in flux.